Dieter Roth

«Black page with holes (poetry machine)»

From Media Art Net:

Dieter Roth developed this piece as a contribution to the Fluxus publication «An Anthology,» which appeared in 1963. When the book was first planned in 1961, he sent to George Maciunas a black page with holes in it and the following instructions for use: «please take the sheet with holes in, but do it like this: take any printed matter, for instance pages of book, catalogs, logocats, folders, posters, newspaper, emballage cut in size of fluxus make the holes there in to through, put in to fluxus, loose (as the black sheet) would have been; loose, i mean : don’t take black sheet, take pages of book, catalogs, logocats, folders, posters, newspaper, emballage, tricotage camouflage, cut as fluxus in size, make the holes therein, put into it fluxum, i mean put the loose sheet then into fluxus.» In other words: the black page is intended as a master for perforating found printed material through which changing views will then be available. On publication, «An Anthology» included a «white page with holes» but not the associated printed matter.

«Black page with holes (poetry machine)»

Tuesday, January 22, 2008

Robopoetics

At all events my own essays and dissertations about love

and its endless pain and perpetual pleasure will be

known and understood by all of you who read this and

talk or sing or chant about it to your worried friends

or nervous enemies. Love is the question and the subject

of this essay. We will commence with a question:

does steak love lettuce? This question is implacably

hard and inevitably difficult to answer.

RACTER

At all events my own essays and dissertations about love

and its endless pain and perpetual pleasure will be

known and understood by all of you who read this and

talk or sing or chant about it to your worried friends

or nervous enemies. Love is the question and the subject

of this essay. We will commence with a question:

does steak love lettuce? This question is implacably

hard and inevitably difficult to answer.

RACTER

Monday, January 21, 2008

Language as Sculpture, Words as Clay

By RANDY KENNEDY

Published: October 21, 2007, The New York Times

[...]

In a recent interview at his temporary studio, as the construction drill droned on outside, Mr. Weiner, a tall, thin man with a trademark flowing Moses beard, seemed not to notice the noise anymore, speaking in a quiet, smoke-deepened basso-profundo. He said that while people had gradually accepted a wide range of nontraditional materials as being within the realm of sculpture — Mr. Andre’s plain, stacked fire bricks or metal tiles; Dan Flavin’s fluorescent tubes; Bruce Nauman’s painted body — using only language as a material seemed to be going way too far. (Mr. Weiner’s actual way of describing this, evoking his years on the docks, can’t be printed in this newspaper.)

But his use of language was not intended to be confrontational, he said. It was democratic, to make art that was open-ended and able to adapt easily to different contexts and even different cultures. He has made work in dozens of countries, translated into dozens of languages.

“If it’s successful, the work really becomes part of people’s lives,” Mr. Weiner said, relating, as he rolled a cigarette from pouch of tobacco, a story of a late-night cab ride in Vienna. The cabdriver talked proudly about one of Mr. Weiner’s pieces in that city — the words “Smashed to Pieces (in the Still of the Night)” painted in huge letters atop a Nazi-era military tower in 1991 — not knowing or caring, really, who made the work and certainly not realizing that the creator was in the back seat of his cab.

More.

By RANDY KENNEDY

Published: October 21, 2007, The New York Times

[...]

In a recent interview at his temporary studio, as the construction drill droned on outside, Mr. Weiner, a tall, thin man with a trademark flowing Moses beard, seemed not to notice the noise anymore, speaking in a quiet, smoke-deepened basso-profundo. He said that while people had gradually accepted a wide range of nontraditional materials as being within the realm of sculpture — Mr. Andre’s plain, stacked fire bricks or metal tiles; Dan Flavin’s fluorescent tubes; Bruce Nauman’s painted body — using only language as a material seemed to be going way too far. (Mr. Weiner’s actual way of describing this, evoking his years on the docks, can’t be printed in this newspaper.)

But his use of language was not intended to be confrontational, he said. It was democratic, to make art that was open-ended and able to adapt easily to different contexts and even different cultures. He has made work in dozens of countries, translated into dozens of languages.

“If it’s successful, the work really becomes part of people’s lives,” Mr. Weiner said, relating, as he rolled a cigarette from pouch of tobacco, a story of a late-night cab ride in Vienna. The cabdriver talked proudly about one of Mr. Weiner’s pieces in that city — the words “Smashed to Pieces (in the Still of the Night)” painted in huge letters atop a Nazi-era military tower in 1991 — not knowing or caring, really, who made the work and certainly not realizing that the creator was in the back seat of his cab.

More.

Watt

Here he stood. Here he sat. Here he knelt. Here he lay. Here he moved, to and fro, from the door to the window, from the window to the door; from the window to the door, from the door to the window; from the fire to the bed, from the bed to the fire; from the bed to the fire, from the fire to the bed; from the door to the fire, from the fire to the door; from the fire to the door, from the door to the fire; from the window to the bed, from the bed to the window; from the bed to the window, from the window to the bed; from the fire to the window, from the window to the fire; from the window to the fire, from the fire to the window; from the bed to the door, from the door to the bed; from the door to the bed, from the bed to the door; from the door to the window, from the window to the fire; from the fire to the window, from the window to the door; from the window to the door, from the door to the bed; from the bed to the door, from the door to the window; from the fire to the bed, from the bed to the window; from the window to the bed, from the bed to the fire; from the bed to the fire, from the fire to the door; from the door to the fire, from the fire to the bed; from the door to the window, from the window to the bed; from the bed to the window, from the window to the door; from the window to the door, from the door to the fire; from the fire to the door, from the door to the window; from the fire to the bed, from the bed to the door; from the door to the bed, from the bed to the fire; from the bed to the fire, from the fire to the window; from the window to the fire, from the fire to the bed; from the door to the fire, from the fire to the window; from the window to the fire, from the fire to the door; from the window to the bed, from the bed to the door; from the door to the bed, from the bed to the window; from the fire to the window, from the window to the bed; from the bed to the window, from the window to the fire; from the bed to the door, from the door to the fire; from the fire to the door, from the door to the bed.

The room was furnished solidly and with taste.

Samuel Beckett, from Watt [Olympia Press, 1953]

Here he stood. Here he sat. Here he knelt. Here he lay. Here he moved, to and fro, from the door to the window, from the window to the door; from the window to the door, from the door to the window; from the fire to the bed, from the bed to the fire; from the bed to the fire, from the fire to the bed; from the door to the fire, from the fire to the door; from the fire to the door, from the door to the fire; from the window to the bed, from the bed to the window; from the bed to the window, from the window to the bed; from the fire to the window, from the window to the fire; from the window to the fire, from the fire to the window; from the bed to the door, from the door to the bed; from the door to the bed, from the bed to the door; from the door to the window, from the window to the fire; from the fire to the window, from the window to the door; from the window to the door, from the door to the bed; from the bed to the door, from the door to the window; from the fire to the bed, from the bed to the window; from the window to the bed, from the bed to the fire; from the bed to the fire, from the fire to the door; from the door to the fire, from the fire to the bed; from the door to the window, from the window to the bed; from the bed to the window, from the window to the door; from the window to the door, from the door to the fire; from the fire to the door, from the door to the window; from the fire to the bed, from the bed to the door; from the door to the bed, from the bed to the fire; from the bed to the fire, from the fire to the window; from the window to the fire, from the fire to the bed; from the door to the fire, from the fire to the window; from the window to the fire, from the fire to the door; from the window to the bed, from the bed to the door; from the door to the bed, from the bed to the window; from the fire to the window, from the window to the bed; from the bed to the window, from the window to the fire; from the bed to the door, from the door to the fire; from the fire to the door, from the door to the bed.

The room was furnished solidly and with taste.

Samuel Beckett, from Watt [Olympia Press, 1953]

THE UBUWEB :: ANTHOLOGY OF CONCEPTUAL WRITING

introduced and edited by Craig Douglas Dworkin

Poetry expresses the emotional truth of the self. A craft honed by especially sensitive individuals, it puts metaphor and image in the service of song.

Or at least that's the story we've inherited from Romanticism, handed down for over 200 years in a caricatured and mummified ethos - and as if it still made sense after two centuries of radical social change. It's a story we all know so well that the terms of its once avant-garde formulation by William Wordsworth are still familiar, even if its original manifesto tone has been lost: "I have said," he famously reiterated, "that poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings; it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility."

But what would a non-expressive poetry look like? A poetry of intellect rather than emotion? One in which the substitutions at the heart of metaphor and image were replaced by the direct presentation of language itself, with "spontaneous overflow" supplanted by meticulous procedure and exhaustively logical process? In which the self-regard of the poet's ego were turned back onto the self-reflexive language of the poem itself? So that the test of poetry were no longer whether it could have been done better (the question of the workshop), but whether it could conceivably have been done otherwise.

More.

introduced and edited by Craig Douglas Dworkin

Poetry expresses the emotional truth of the self. A craft honed by especially sensitive individuals, it puts metaphor and image in the service of song.

Or at least that's the story we've inherited from Romanticism, handed down for over 200 years in a caricatured and mummified ethos - and as if it still made sense after two centuries of radical social change. It's a story we all know so well that the terms of its once avant-garde formulation by William Wordsworth are still familiar, even if its original manifesto tone has been lost: "I have said," he famously reiterated, "that poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings; it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility."

But what would a non-expressive poetry look like? A poetry of intellect rather than emotion? One in which the substitutions at the heart of metaphor and image were replaced by the direct presentation of language itself, with "spontaneous overflow" supplanted by meticulous procedure and exhaustively logical process? In which the self-regard of the poet's ego were turned back onto the self-reflexive language of the poem itself? So that the test of poetry were no longer whether it could have been done better (the question of the workshop), but whether it could conceivably have been done otherwise.

More.

Picture Writing

[I]t is quite beyond doubt that the development of writing will not indefinitely be bound by the claims to power of a chaotic academic and commercial activity; rather, quantity is approaching the moment of a qualitative leap when writing, advancing ever more deeply into the graphic regions of its new eccentric figurativeness, will take sudden possession of an adequate factual content.

In this picture writing, poets, who will now as in earliest times be first and foremost experts in writing, will be able to participate only by mastering the fields in which (quite unobtrusively) it is being constructed: the statistical and technical diagram. With the foundation of an international moving script they will renew their authority in the life of peoples, and find a role awaiting them in comparison to which all the innovative aspiration of rhetoric will reveal themselves as antiquated day-dreams.

Walter Benjamin, 'Attested Auditor' in One-Way Street, Selected Writings, p. 456-7, OWS p. 63f

[I]t is quite beyond doubt that the development of writing will not indefinitely be bound by the claims to power of a chaotic academic and commercial activity; rather, quantity is approaching the moment of a qualitative leap when writing, advancing ever more deeply into the graphic regions of its new eccentric figurativeness, will take sudden possession of an adequate factual content.

In this picture writing, poets, who will now as in earliest times be first and foremost experts in writing, will be able to participate only by mastering the fields in which (quite unobtrusively) it is being constructed: the statistical and technical diagram. With the foundation of an international moving script they will renew their authority in the life of peoples, and find a role awaiting them in comparison to which all the innovative aspiration of rhetoric will reveal themselves as antiquated day-dreams.

Walter Benjamin, 'Attested Auditor' in One-Way Street, Selected Writings, p. 456-7, OWS p. 63f

Fools lament the decay of criticism. … Criticism is a matter of correct distancing…. Today the most real, the mercantile gaze into the heart of things is the advertisement. It abolishes the space where contemplation moved and all but hits us between the eyes with things as a car, growing to gigantic proportions, careens at us out of a film screen. … [P]eople whom nothing moves or touches any longer are taught to cry again by films. … What, in the end, makes advertisements so superior to criticism? Not what the moving red neon sign says—but the fiery pool reflecting it in the asphalt."

Walter Benjamin, 'This Space for Rent' (in One-Way Street, Selected Writings, p. 476)

Walter Benjamin, 'This Space for Rent' (in One-Way Street, Selected Writings, p. 476)

Stephen Mallarmé: "Un Coup de Dés / jamais n' abolira le Hasard" ("The Dice Throw / Will Never abrogate Chance" 1914)

The typographical exaggeration of "Un Coup de Dés...." was a calculated attempt to force the viewer to encounter blank page space as a compositional element within an illusionistic picture plane. "Un Coup de Dés...."effectively reduced the legibility of the written word to that of a typographic pattern, text is marginalised to such an extent that the viewer is forced both literally and metaphorically to read between the lines. The layout and graphic overprinting of "Un Coup de Dés..." deliberately renders text illegible as naturalistic or figural narrative and this is confirmed by Mallarmé's description of the work as a constellation or shipwreck.

from Concrete Poetry and Conceptual Art: A Spectre at the Feast?

by Neil Powell

The typographical exaggeration of "Un Coup de Dés...." was a calculated attempt to force the viewer to encounter blank page space as a compositional element within an illusionistic picture plane. "Un Coup de Dés...."effectively reduced the legibility of the written word to that of a typographic pattern, text is marginalised to such an extent that the viewer is forced both literally and metaphorically to read between the lines. The layout and graphic overprinting of "Un Coup de Dés..." deliberately renders text illegible as naturalistic or figural narrative and this is confirmed by Mallarmé's description of the work as a constellation or shipwreck.

from Concrete Poetry and Conceptual Art: A Spectre at the Feast?

by Neil Powell

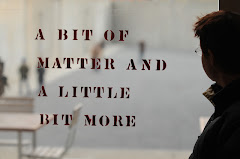

Lawrence Weiner

Essay by Lynne Cooke

Since 1967 Lawrence Weiner's work has been formulated by recourse to language rather than the more conventional idioms of painting or sculpture. In language, Weiner found a medium and tool for representing material relationships in the external world in as objective a manner as possible, one that could eliminate all references to authorial subjectivity—all traces of the artist's hand, his skill, or his taste. "ART IS NOT A METAPHOR UPON THE RELATIONSHIP OF HUMAN BEINGS TO OBJECTS & OBJECTS TO OBJECTS IN RELATION TO HUMAN BEINGS BUT A REPRESENTATION OF AN EMPIRICAL EXISTING FACT," he argues. "IT DOES NOT TELL THE POTENTIAL & CAPABILITIES OF AN OBJECT (MATERIAL) BUT PRESENTS A REALITY CONCERNING THAT RELATIONSHIP."1 This often-quoted contention is spelled out in characteristically succinct spare terms: it posits the allusive and hypothetical as the negative of that which is, an objectively observable or verifiable concrete reality.

More.

Essay by Lynne Cooke

Since 1967 Lawrence Weiner's work has been formulated by recourse to language rather than the more conventional idioms of painting or sculpture. In language, Weiner found a medium and tool for representing material relationships in the external world in as objective a manner as possible, one that could eliminate all references to authorial subjectivity—all traces of the artist's hand, his skill, or his taste. "ART IS NOT A METAPHOR UPON THE RELATIONSHIP OF HUMAN BEINGS TO OBJECTS & OBJECTS TO OBJECTS IN RELATION TO HUMAN BEINGS BUT A REPRESENTATION OF AN EMPIRICAL EXISTING FACT," he argues. "IT DOES NOT TELL THE POTENTIAL & CAPABILITIES OF AN OBJECT (MATERIAL) BUT PRESENTS A REALITY CONCERNING THAT RELATIONSHIP."1 This often-quoted contention is spelled out in characteristically succinct spare terms: it posits the allusive and hypothetical as the negative of that which is, an objectively observable or verifiable concrete reality.

More.

Word Salad

The Dadaists attached much less importance to the sales value of their work than to its usefulness for contemplative immersion. The studied degradation of their material was not the least of their means to achieve this uselessness. Their poems are “word salad” containing obscenities and every imaginable waste product of language. The same is true of their paintings, on which they mounted buttons and tickets. What they intended and achieved was a relentless destruction of the aura of their creations, which they branded as reproductions with the very means of production.

Walter Benjamin (1936), from "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction"

The Dadaists attached much less importance to the sales value of their work than to its usefulness for contemplative immersion. The studied degradation of their material was not the least of their means to achieve this uselessness. Their poems are “word salad” containing obscenities and every imaginable waste product of language. The same is true of their paintings, on which they mounted buttons and tickets. What they intended and achieved was a relentless destruction of the aura of their creations, which they branded as reproductions with the very means of production.

Walter Benjamin (1936), from "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction"

The Well-Shaped Phrase as Art

By ROBERTA SMITH

Published: November 16, 2007, New York Times

...Be grateful, then, for Lawrence Weiner’s mind-stretching 40-year retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, which is respite, wake-up call and purification rite all in one. It should be required viewing for anyone interested in today’s art, especially people who frequent contemporary art auctions.

A joint effort of the Whitney and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, this profuse exhibition has been organized by Donna De Salvo, the Whitney’s chief curator, and Ann Goldstein, the Los Angeles museum’s senior curator. It honors a Conceptual artist who has made history, and plenty of memorable artworks, while influencing Barbara Kruger, Felix Gonzalez-Torres and Tony Feher, among others. Yet Mr. Weiner has largely and quite deliberately skipped over the production and marketing of salable, portable, immutable objects.

The show consists primarily of cryptic yet suggestive phrases in large letters, splayed across walls, ceiling beams and occasionally floors, that conjure up various physical situations but often leave to your imagination the objects or the scale involved. “A Turbulence Induced Within a Body of Water” could be hands splashing in a bathtub or a tanker churning waves behind it. “Encased By + Reduced to Rust” evokes a crumbling object, but it could also be a soul or an artist’s talent. (And there is that twist of “rust” where you expect “dust.”)

More.

By ROBERTA SMITH

Published: November 16, 2007, New York Times

...Be grateful, then, for Lawrence Weiner’s mind-stretching 40-year retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, which is respite, wake-up call and purification rite all in one. It should be required viewing for anyone interested in today’s art, especially people who frequent contemporary art auctions.

A joint effort of the Whitney and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, this profuse exhibition has been organized by Donna De Salvo, the Whitney’s chief curator, and Ann Goldstein, the Los Angeles museum’s senior curator. It honors a Conceptual artist who has made history, and plenty of memorable artworks, while influencing Barbara Kruger, Felix Gonzalez-Torres and Tony Feher, among others. Yet Mr. Weiner has largely and quite deliberately skipped over the production and marketing of salable, portable, immutable objects.

The show consists primarily of cryptic yet suggestive phrases in large letters, splayed across walls, ceiling beams and occasionally floors, that conjure up various physical situations but often leave to your imagination the objects or the scale involved. “A Turbulence Induced Within a Body of Water” could be hands splashing in a bathtub or a tanker churning waves behind it. “Encased By + Reduced to Rust” evokes a crumbling object, but it could also be a soul or an artist’s talent. (And there is that twist of “rust” where you expect “dust.”)

More.

Tuesday, January 15, 2008

Dartington College of Arts specialises in teaching, practice and research in contemporary performance arts. This includes practices that may not conventionally be thought of as ‘performance’ arts but which can have a very close relationship with performance practices and/or which can take on innovative approaches when developed in an environment of performance. This has been the context for writing at Dartington. When designing a new undergraduate writing award for a 1994 start we chose to adopt as a name for the award and for a new field of writing a term that was already in use at the College: Performance Writing.

More.

More.

Friday, January 11, 2008

Pierre Bayard's How to Talk About Books You Haven't Read is an invaluable guide to subverting the reading classes, says Toby Lichtig

Sunday January 6, 2008

The Observer

How to Talk About Books You Haven't Read

by Pierre Bayard; translated by Jeffrey Mehlman

Granta £12, pp185

Pierre Bayard is a Paris-based professor of French literature. As such, he is a practised charlatan, a literary bullshitter, a professional 'non-reader'. 'Because I teach literature at university level,' he says, regretfully, 'there is, in fact, no way to avoid commenting on books that most of the time I haven't even opened.'

Bayard is infiltrating a 'forbidden subject', an area equivalent to 'finance and sex' in its secrecy. Despite society's 'worship' of reading, he avers, we are most of us heathens, even among the literary elite. And quite right, too: why waste time reading Joyce and Proust when you can talk about them - or skim the work of others? Taking it as given that no one actually reads for the pleasure of the process, Bayard proceeds to investigate the meaning of bibliographic cultural capital.

More.

Sunday January 6, 2008

The Observer

How to Talk About Books You Haven't Read

by Pierre Bayard; translated by Jeffrey Mehlman

Granta £12, pp185

Pierre Bayard is a Paris-based professor of French literature. As such, he is a practised charlatan, a literary bullshitter, a professional 'non-reader'. 'Because I teach literature at university level,' he says, regretfully, 'there is, in fact, no way to avoid commenting on books that most of the time I haven't even opened.'

Bayard is infiltrating a 'forbidden subject', an area equivalent to 'finance and sex' in its secrecy. Despite society's 'worship' of reading, he avers, we are most of us heathens, even among the literary elite. And quite right, too: why waste time reading Joyce and Proust when you can talk about them - or skim the work of others? Taking it as given that no one actually reads for the pleasure of the process, Bayard proceeds to investigate the meaning of bibliographic cultural capital.

More.

Monday, January 07, 2008

ekphrasis

If the dialectic of word and image is central to the study of media, then the term ekphrasis (alternatively spelled ecphrasis) must also be a crucial part of understanding media as the intersection of verbal and visual. Few pieces of media jargon have as long a history or as considerable an evolution as ekphrasis. The conflict of word and image in media can be better understood by tracing the history and evolution of ekphrasis, which embodies the practice of both elements.

Ryan Welsh (2007)

If the dialectic of word and image is central to the study of media, then the term ekphrasis (alternatively spelled ecphrasis) must also be a crucial part of understanding media as the intersection of verbal and visual. Few pieces of media jargon have as long a history or as considerable an evolution as ekphrasis. The conflict of word and image in media can be better understood by tracing the history and evolution of ekphrasis, which embodies the practice of both elements.

Ryan Welsh (2007)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)